The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) was the seminal event of twentieth-century Mexico. It began with armed revolts from one end of the country to the other and a military coup and summary execution of the elected president and vice-president, Francisco I. Madero and José Pino Suárez. It ended with the deaths of some of the most key members of the revolution, including Pascual Orozco, Emiliano Zapata, Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, and Álvaro Obregón. For the purposes of our exploration of social bandits, rebels, and revolutionaries, we point out that the conflict featured a cast of history makers each of whom in turn transformed from outlaw into respectable political leader and who, in most cases, was overthrown by a new outlaw turned power broker.

The Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) was the seminal event of twentieth-century Mexico. It began with armed revolts from one end of the country to the other and a military coup and summary execution of the elected president and vice-president, Francisco I. Madero and José Pino Suárez. It ended with the deaths of some of the most key members of the revolution, including Pascual Orozco, Emiliano Zapata, Venustiano Carranza, Pancho Villa, and Álvaro Obregón. For the purposes of our exploration of social bandits, rebels, and revolutionaries, we point out that the conflict featured a cast of history makers each of whom in turn transformed from outlaw into respectable political leader and who, in most cases, was overthrown by a new outlaw turned power broker.

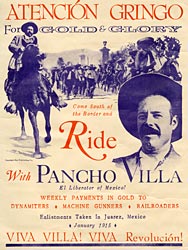

Francisco "Pancho" Villa helped oust the aged Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz with an attack in 1911 upon Ciudad Juárez across the border from Texas, with many El Paso residents able to watch Villa's victory firsthand from atop railroad cars and the roofs of buildings. Villa became the subject of much interest among U.S. citizens, morphing in the popular imagination from bandit leader to heroic general who sought American volunteers for his army. However, after his March 1915 incursion into the United States and attack on Columbus, New Mexico, he immediately was demonized as an outlaw and arrogant invader of the U.S. Southwest.

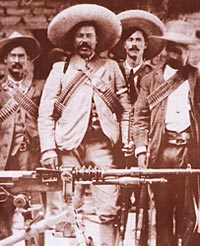

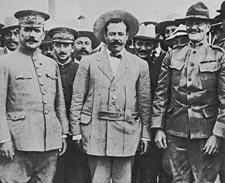

In these images we can see something of this metamorphosis, beginning with an informal appearance after the battle at Ciudad Juárez. Next we see the adoption of a military appearance as Villa posed with some of his men in  one picture and in another with General Álvaro Obregón and U.S. General John "Black Jack" Pershing, who would later lead the 1916-17 Punitive Expedition against Villa.

one picture and in another with General Álvaro Obregón and U.S. General John "Black Jack" Pershing, who would later lead the 1916-17 Punitive Expedition against Villa.

Pascual Orozco was an initial supporter of Francisco I. Madero in his campaign for election against Porfirio Díaz. Winning a battle against a general loyal to Díaz, Orozco eventually became a general himself among the rebel troops supporting Madero, having at one point Pancho Villa as one of his subordinates. He had a falling out with Madero and then actively opposed him beginning in 1912, supporting his rebellion against Madero by stealing cattle in Mexico and selling them across the border in Texas. Orozco was defeated in battle by Victoriano Huerta, who was then following the orders of President Madero before he turned against his president and had Madero killed. Orozco fled to the United States, only to return and fight for Huerta against Villa when the former became president after Madero's execution. As a general for Huerta, Orozco actually enjoyed several victories against the Constitutionalists, but despite this, Huerta was eventually deposed and Orozco again fled to the United States. While in Texas, after being accused of horse theft, Orozco and his remaining men were killed in 1915 in a shootout with a force of U.S. Army cavalrymen and Texas Rangers.  Each of these figures, Francisco I. Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Pascual Orozco, was alternately a member of the ruling government and a despised enemy of Mexico after a new ruling regime was established by force.

Each of these figures, Francisco I. Madero, Victoriano Huerta, and Pascual Orozco, was alternately a member of the ruling government and a despised enemy of Mexico after a new ruling regime was established by force.

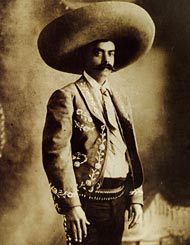

Emiliano Zapata took up arms against Porfirio Díaz, fighting to redress long-standing grievances of Mexican Amerindians related to Porfirian policy that allowed usurpation of their traditional lands by wealthy Mexican hacendados and foreign investors. With the slogan "Tierra y libertad" [Land and Liberty], a nod toward anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón's work, the zapatistas blazed across southern Mexico. Though not affecting a military appearance as did Villa, Emiliano Zapata was no less aware of his political and martial importance to the revolutionary movement, as one may see in the images below. We see Zapata posing in a studio in his characteristic charro suit and again in a second image, while supporters wait in the background, this time adorned with saber, rifle, bandoliers, and the national colors. He was already endowed with the glow of immortality. We see Zapata, shortly before his visit with Pancho Villa in Mexico City, seated between General Benjamín  Argumedo in a military uniform on the left and Colonel Manuel Palafox on the right, and, standing behind them from left to right, Ignacio Ocampo Amezcua, U.S. consul George Carothers, and Amador Salazar. We see him beside his brother Eufemio Zapata in another photograph, and in the last photograph we see him finally without a sombrero, though no less charro for it, seated next to a tense President Eulalio Gutiérrez (with glasses) and Pancho Villa. He was at the height of his power and then most dangerous to the landed elite who had ruled Mexico since its founding.

Argumedo in a military uniform on the left and Colonel Manuel Palafox on the right, and, standing behind them from left to right, Ignacio Ocampo Amezcua, U.S. consul George Carothers, and Amador Salazar. We see him beside his brother Eufemio Zapata in another photograph, and in the last photograph we see him finally without a sombrero, though no less charro for it, seated next to a tense President Eulalio Gutiérrez (with glasses) and Pancho Villa. He was at the height of his power and then most dangerous to the landed elite who had ruled Mexico since its founding.

Despite having occupied Mexico City and the presidential palace in 1914, Zapata was routed frequently in battles by the forces under Venustiano Carranza and ultimately betrayed and killed in an ambush. Considered an outlaw by the ruling government in 1919, he rose again as the purest martyr to the Mexican Revolution and of the indigenous people of Mexico.

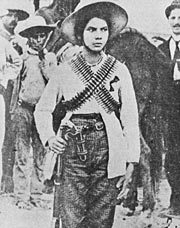

The Mexican Revolution had no less of a profound impact upon its people than on its leaders. An estimated 1 million Mexicans, of the then total population of 15 million, died during the conflict. It was not restricted to  geographic region, class, age, or even sex, as men, women, and even children took up arms at one point or another to decide the political future or settle old scores. Some of the young men who took up arms, unlike the women who served in the revolutionary armies, would go on to enjoy political careers that were based on the claim that they were patriots of the first order. Future President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) was one such figure who could claim true revolutionary roots (see the photograph of him with rifle, pistol, and bandolier), eventually becoming the most popular of revolutionary presidents for supporting urban workers, redistributing land to the rural poor, and nationalizing foreign-owed railroads and oil fields.

geographic region, class, age, or even sex, as men, women, and even children took up arms at one point or another to decide the political future or settle old scores. Some of the young men who took up arms, unlike the women who served in the revolutionary armies, would go on to enjoy political careers that were based on the claim that they were patriots of the first order. Future President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940) was one such figure who could claim true revolutionary roots (see the photograph of him with rifle, pistol, and bandolier), eventually becoming the most popular of revolutionary presidents for supporting urban workers, redistributing land to the rural poor, and nationalizing foreign-owed railroads and oil fields.

As the war spread and brutalized countless communities and families, the fighters' ranks were filled by women who proved themselves just as tough as their male comrades.

These women represented the peasantry, the working poor, and intellectuals from the middle or upper classes. Coronela María de la Luz Espinosa Barrera was one of the very few revolutionaries who received a pension as a veteran of the Mexican Revolution, having served with much distinction. However, she had survived all those battles only to find herself  and her lifestyle socially unacceptable in peacetime. For one who "smoked, drank, gambled and feared no man" to revert to the timid submissiveness expected of women was unthinkable. Like many veterans, María found conformity impossible and spent the rest of her life as "a restless soul," an itinerant peddler still dressed as a man and carrying a pistol.

and her lifestyle socially unacceptable in peacetime. For one who "smoked, drank, gambled and feared no man" to revert to the timid submissiveness expected of women was unthinkable. Like many veterans, María found conformity impossible and spent the rest of her life as "a restless soul," an itinerant peddler still dressed as a man and carrying a pistol.

In 1910 Margarita Neri led a force of over 1,000, sweeping through Tabasco and Chiapas, looting, burning, and killing. These were hardly unusual events in wartime, except for the fact that this particular group's commander, brandishing a bloody machete and vowing to decapitate Díaz, was a woman. Margarita Neri earned such a reputation for ruthless slaughter that the governor of Guerrero, on hearing of her approach, hid in a crate and was sneaked out of town.

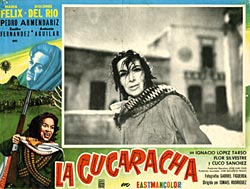

Many of the armed women of the revolution were unnamed except by their apodos, often because they were outlaws and leaders of bandit gangs before and during the revolution or because they had killed to avenge their dead men. These include La Coronela, La Chata, La Güera Carrasco, La Corredora, and La Valentina. In turn, these anonymous women or composites of different figures were brought into popular culture by way of the songs of the period and films that treat the revolution. Examples of films that will be examined later include La Adelita, La Cucaracha, La Valentina (1940, starring Jorge Negrete and Esperanza Baur)and La Soldadera. Other armed women appear in films such as Los de abajo and La Negra Angustias; these are composite fictional characters modeled on actual tough hembras.

Many of the armed women of the revolution were unnamed except by their apodos, often because they were outlaws and leaders of bandit gangs before and during the revolution or because they had killed to avenge their dead men. These include La Coronela, La Chata, La Güera Carrasco, La Corredora, and La Valentina. In turn, these anonymous women or composites of different figures were brought into popular culture by way of the songs of the period and films that treat the revolution. Examples of films that will be examined later include La Adelita, La Cucaracha, La Valentina (1940, starring Jorge Negrete and Esperanza Baur)and La Soldadera. Other armed women appear in films such as Los de abajo and La Negra Angustias; these are composite fictional characters modeled on actual tough hembras.

References

Hobsbawm, Eric (J.). Bandits. New York: The New Press, 2000. Fourth revised edition.

———. Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries. Manchester, G.B.: Manchester University Press, 1959. 2nd ed. New York: Praeger,1963. 3rd ed. Manchester, G.B.: Manchester University Press, 1971.

———. Revolutionaries: Contemporary Essays. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1973.