The Mexican Revolution of 1910 was the most significant event in modern Mexican history, and it affected every sector and walk of life in Mexican society. This revolution, which lasted from 1910 to 1920 approximately, proved to be a fertile proving ground for the emergence of Mexican guerreras, those who were good, good-bad, and rather vicious. As a practical matter, we have separated the historical persons from their filmic interpretations.

Mexican Guerreras in the History of the Mexican Revolution of 1910

In recent decades the pace of research on the Mexican guerreras during the Revolution of 1910 has been dynamic and prodigiously expanding. These women represented the gamut of the social strata. They were peasants, the working poor, and intellectuals from the middle or upper classes. They were depicted in the warrior aspect as coronelas and generalas and rieleras and soldaderas, and as both heroic and nonheroic. Moreover, the heroic women were many, and their stories prompted adaptation in popular culture. We have classified these figures according to the same system that we describe in the introduction to this Web site: historical figures who have been more or less expanded in the magnitude of their actions and personalities, pseudo-historical, composite, and outright fictional personages.

The “heroic women” described here have a basis in history. They generally have been notable either for their violent and “sinful” ways, comparable to their male counterparts, or for feminist activities, especially among the clases letradas but occasionally among the less educated. Here are some tough hembras.

Coronela María de la Luz Espinosa Barrera was one of the very few revolutionaries who received a pension as a veteran of the Mexican Revolution, having served with such distinction. However, she had survived all those battles only to find herself and her lifestyle socially unacceptable in peacetime. For one who “smoked, drank, gambled and feared no man” to revert to the timid submissiveness expected of women was unthinkable. Like many veterans, Maria found conformity impossible and spent the rest of her life as “a restless soul,” an itinerant peddler dressed as a man and carrying a pistol.

Margarita Neri led a force of more than 1,000 in 1910, sweeping through Tabasco and Chiapas looting, burning, and killing. These were hardly unusual events in wartime, except for the fact that this particular group’s commander, who brandished a bloody machete and vowed to decapitate Díaz, was a woman. Margarita Neri earned such a reputation for ruthless slaughter that the governor of Guerrero, on hearing of her approach, hid himself in a crate and was sneaked out of town. Some say that she served as an officer under Zapata. The judgment of popular history is that she deserves the accolade of “a superb guerilla commander.”

A weapons expert, crack shot, and nurse, Margarita Ortega teamed with her daughter, Rosaura Gortari, and they both served as couriers and spies. However, they fought on the losing side against Madero. Captured by the Maderistas, they were forced to march into the desert and were left without food or water. They survived the ordeal, but Rosaura died soon after reaching refuge in Phoenix. Margarita did not live much longer. Sent on another mission into Sonora, she was recaptured. Forced to stand in a cage where she was poked, prodded, and savagely beaten, she refused to betray her comrades and after four days of torture was summarily executed.

A different sort of bravery was exhibited by the heroic nurse of the Dorados, Beatriz González Ortega, who refused to distinguish between federales and villistas despite being whipped and threatened with death. Villa eventually treated González with respect, and numerous primary schools, nursing schools, streets, and villages carry her name, a public acknowledgment of her courage and humanity.

Many of the armed women of the Revolution were unnamed except by their apodos, often because they were outlaws and leaders of bandit gangs before and during the revolution or who had killed to avenge the deaths of their men. La Coronela, La Chata, La Güera Carrasco, La Corredora, and La Valentina are examples of such women. In turn these anonymous women (or composites of different figures) were brought into popular culture, including in the songs of the period and in films that treat the Revolution

Mexicana intellectuals also had major roles in the Revolution of 1910. Flores de Andrade, a member of the Hijas de Cuauhtémoc and eventually an ally of Francisco I. Madero, was a rebel who, after inheriting her wealthy grandparents' estate, immediately gave "absolute liberty" to all the peasants who had worked on the estate and supplied them with tools and animals to continue to work the land as long as they wished. She was an ardent member of a secret society whose aim was to overthrow Porfirio Díaz and achieve freedom for all Mexicans. To this end, she marched and petitioned so successfully that she aroused both Díaz and the U.S. officials who supported him. Hunted by both, she sought refuge in the north but was eventually captured and sentenced to death. A presumably apocryphal tall tale about her is that upon facing the firing squad, she allegedly grabbed the commander’s rifle, forced his men to put down their weapons and held out until President Taft ordered her release! However improbable, she did survive to tell her story. Her oral history, as recounted to Mexican anthropologist Manuel Gamio, has provided insights into the political activism of women among Mexican political refugees in Texas in the early twentieth century.

Elisa Acuña y Roseta (1887–1946) was an associate of anarchist Antonio Díaz Soto y Gama, one of the primary intellectual spokespersons for Emiliano Zapata and zapatismo. Along withfeminist, political radical, and iconoclast Juana Belén Gutiérrez de Mendoza (1875–1942), she cofounded the journal Vésper, Justicia y Libertad, often praised by Flores Magón’s journal, Regeneración. Both Acuña and Belén Gutiérrez were imprisoned by the Díaz government, and from jail edited the socialist newspaper Fiat Lux. After the Victoriano Huerta coup, Acuña wrote propaganda for La Voz de Juárez, Sinfonía, and Combate y Anáhuac until Obregón’s triumphant entry into Mexico City in August 1914, at which time she joined the Zapatistas and served as a liaison between them and the carrancistas and as the head of propaganda in Puebla. In the 1920s she participated in the Consejo Feminista Mexicano and the Liga Panamericana de Mujeres.

An associate of Acuña and of Belén Gutiérrez was Mexican American poet and political figure Sara Estela Ramírez (1881–1910), who, despite dying of unknown causes after an illness at the age of 29, was a leader of the Partido Liberal Mexicano, a member of the feminist organization Regeneración y Concordia, and the publisher of two newspapers, La Corregidora and Aurora. In addition to her political activities, she wrote poetry that evoked the bicultural nature of Tejano life along the border.

Hermila Galindo de Topete (1896–1954) was the cofounder and editor of the feminist and pro-Carranza journal Mujer Moderna and was one of Carranza's most energetic and visible collaborators and propagandists. She eventually wrote his biography in addition to at least five other books. Galindo was an early supporter of many radical feminist issues such as sex education in the schools, women's suffrage, and divorce. She was one of the first feminists to bluntly state that the Catholic Church was the main obstacle to the advancement of feminism in Mexico.

Dolores Jiménez y Muro (1848–1925) was a member of the editorial staff of the feminist journal La Mujer Mexicana, a leader in the Liga Feminina Anti-reelectionista "Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez" and the president of the Hijas de Cuauhtémoc. Both groups were actively anti-Díaz and the Hijas were arrested in September 1910 during a large but peaceful march in Mexico City protesting Díaz's policies. Their manifesto called for the political enfranchisement of Mexican women in their "economic, physical, intellectual and moral struggles." In 1911, Jiménez founded the group Regeneración y Concordia from her prison cell. The group's purpose was to "improve the lot of indigenous races, campesinos, obreros, unify revolutionary forces, and elevate women economically, morally and intellectually," In March 1911, Jiménez wrote a political and social plan that promoted bringing Madero to power through organized rebellion near Mexico City. Her plan was unusual because it outlined the need for extensive social and economic reforms rather than simply stating the desire for political change at the top. She specifically recognized in the plan that the daily wages of both men and women in urban and rural areas needed to be increased, as women made up more of the "economically active" population than was acknowledged by the official census. Emiliano Zapata was very enthusiastic about Jiménez's plan, particularly the part calling for the restitution of usurped village lands, and invited her to join his cause in Morelos. She did so after the death of Madero in 1913, and remained there until Zapata's assassination in 1919, well after her seventieth birthday.

The Filmic Depiction of Mexican Guerreras of the Revolution of 1910

Mexican guerreras and women less warlike are very commonly depicted in the enormous cycle of films about the Mexican Revolution of 1910.

One Mexican actress is highly illustrative: María Félix had major roles as a Mexican guerrera in La Cucaracha (1958, directed by Ismael Rodríguez, cinematography by Gabriel Figueroa, and starring María Félix, Dolores del Río, Emilio “Indio” Fernández, Antonio Aguilar, Pedro Armendáriz, and Ignacio López Tarso) depicts the relationship that is established between the hard-fighting, rifle-wielding, drinking, cursing, but also promiscuous Cucaracha (María Félix), who dresses like a man and is committed to the Revolution even unto death, and coronel Zeta, a committed, traditional male revolutionary. The widow Isabel (Dolores del Río), dressed in black, a “good” woman who cries and cries ends up taking coronel Zeta from the "hembra bravía," la Cucaracha.

Other movies related to the Mexican Revolution of 1910 in which María Félix starred include:

La generala (1971)

La Valentina (1966)

La bandida 1963)

Juana Gallo (1961)

La Cucaracha (1959)

La escondida (1956)

Enamorada (1946)

Adelita, La Valentina (1940, starring Jorge Negrete and Esperanza Baur)and La Soldadera, discussed later, are also examples of guerrera stories of the Mexican Revolution of 1910.Other armed women who appear in films such as Los de abajo and La Negra Angustias are composite fictional characters modeled on actual tough hembras.

In Mariano Azuela’s novel Los de abajo (1915), set in the same cauldron of 1910, we meet the smoking, drinking, and fighting “La Pintada,” who is treated like a man by the other soldiers and who contrasts mightily with the other main female character, Camila, a more conventional “victim.” La Pintada eventually is killed without remorse. The novel was adapted into a film of the same name in 1940 (directed by Chano Urueta).

The film Enamorada (1946, directed by Emilio “Indio” Fernández, cinematography by Gabriel Figueroa, and starring María Félix and Pedro Armendáriz), which is somewhat akin to Shakespeare’s Taming of the Shrew, features Beatriz, the daughter of an hacendado who despises pelados and revolucionarios alike. She is “tamed” by José Juan, the revolutionary commander who comes into the region and defends the poor because they are humble and true. For José Juan, conquering Beatriz is a challenge not unlike winning a battle in the Revolution, and he is willing to suffer the slaps and injuries to his macho persona with the certainty that eventually he will tame this "wild mare." The film ends with the proud Beatriz, repudiating her class, leaving family and her fiancé (a goofy kind of gringo no less!) behind, and going with her man on foot at the side of his horse, as a soldadera, a type that she formerly held in contempt. Is this a film about a noble bandida? Well, yes and no. Mostly no, with the attenuating circumstance that despite her subjugation by “love” to male authority, Beatriz is moved by the impetus for social justice revealed by the Revolution and spurns the values and comfort of the hacendado class that formerly had her allegiance.

In 1944 Francisco Rojas González published what has been billed as the first novel of the Mexican Revolution that has a woman, coronela Angustias Farrera, as the main protagonist. The novel's title, La negra Angustias, is ingenious. "Negra" here indicates a woman of dark complexion (usually dark in the Mexican sense, which is possibly mulatto) with the name "Angustias," and the double entendre that results is either “dark Angustias” or "acute anguish." The novel was adapted into a film in 1949 (starring María Elena Marqués as Angustias and Agustín Isunza as her friend, el Huitlacoche) with the same title, directed by the notable female director Matilde Landeta. In the film, the young and attractive Angustias, daughter of the “generoso bandido” Antón Farrera, is marginalized because she lives with the witch Cresencia and because she shuns the predatory males in her midst. Upon knifing to death a charro who attempts to violate her, she flees and becomes a Zapatista soldier, rising to coronela and following the noble teachings of her father, giving justice to women and campesinos alike.

The film La Negra Angustias is notable for its attention to the roles that are culturally assigned to the sexes. In other films of the same period that are superficially similar (Enamorada, La soldadera) the female characters do not often get beyond lamenting their female condition. La Negra Angustias takes the initiative with respect to male domination. When Angustias apprehends “El Picado,” who years earlier had advanced himself on her, she orders that he be castrated in the name of the other “viejas” who he had taken advantage of—Piedad, Rosa, Lupe from Agua Fria—"because only then are men less evil." In another scene, she orders the execution of a prisoner but his fiancée pleads “woman to woman” for him to be freed. Angustias is undeterred but when the girl tells her she is pregnant and that her child will become an orphan before he is born, Angustias softens and frees the man.

taken advantage of—Piedad, Rosa, Lupe from Agua Fria—"because only then are men less evil." In another scene, she orders the execution of a prisoner but his fiancée pleads “woman to woman” for him to be freed. Angustias is undeterred but when the girl tells her she is pregnant and that her child will become an orphan before he is born, Angustias softens and frees the man.

La Soldadera, (1966, directed by José Bolaños, cinematography by Alex Phillips, and starring Silvia Pinal and Narciso Busquets) is an emphatically traditional film in its roles for females, although for a time Lázara (Silvia Pinal), whose husband is killed by the Villistas, takes up arms with them before she comes into the authority of a new Villista who disarms her and gives her conventional roles.

La Adelita occupies a fluid, amorphous place between fiction and history. The most famous song of the Mexican Revolution of 1910 was “La Adelita,” some of which goes as follows:

En lo alto de la abrupta serranía,

acampado se encontraba un regimiento,

y una moza que valiente lo seguía

locamente enamorada del sargento.

Popular entre la tropa era Adelita,

la mujer que el sargento idolatraba,

porque a más de ser valiente era bonita,

que hasta el mismo coronel la respetaba.

Y se oía que decía

aquel que tanto la quería:

Y si Adelita se fuera con otro,

la seguiría por tierra y por mar;

si por mar en un buque de guerra,

si por tierra en un tren militar.

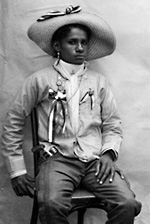

The identity of La Adelita changes according to circumstance. Some had her as a shy 14-year-old nurse, others as a vicious 21-year-old killer. She was variously a harlot, a saint, the sweetheart of the regiment, or Pancho Villa’s private paramour. Although there is a photograph identified as Adelita, there is no proof that this most famous of soldaderas actually existed. Certainly, the glamorous heroine of song and story never did. Many of her purported exploits happened, but to other women who remain faceless and unsung. In time, the name denoted any female soldier, so in a sense the revolutionary Everywoman Adelita not only existed, but also, as another song put it, “Adelita never dies!”

In 1948 the Adelita mythos and, of course, the corrido were the basis of the comedia ranchera film Si Adelita se fuera con otro (directed by Chano Urueta and starring Jorge Negrete and Gloria Marín). Here, Adelita is a rich girl (the plot has shades of Enamorada starring Maria Félix) who leaves home to follow her husband, and disappears but at the end comes back to a rousing chorus of “Adelita,” as she and Negrete are reunited.